“But why do we need copyeditor?” a client asked. “Your work is very clean already and it just adds expense.”

Fair point. My work is clean—but not book-quality clean.

A blog post, for example, can handle a typo or inconsistency. The article is usually read quickly and in the moment. If a correction is needed, it’s as simple as making the change and pressing Update.

With a book, once it’s out in the world, it’s out in the world. Even with the flexibility self-publishing offers, making corrections should be the exception rather than the rule. It’s simply not efficient.

For me, a book requires more rigorous editorial standards than a blog post does. Not only do most books require copyediting, they require multiple types of editing.

Types of editing

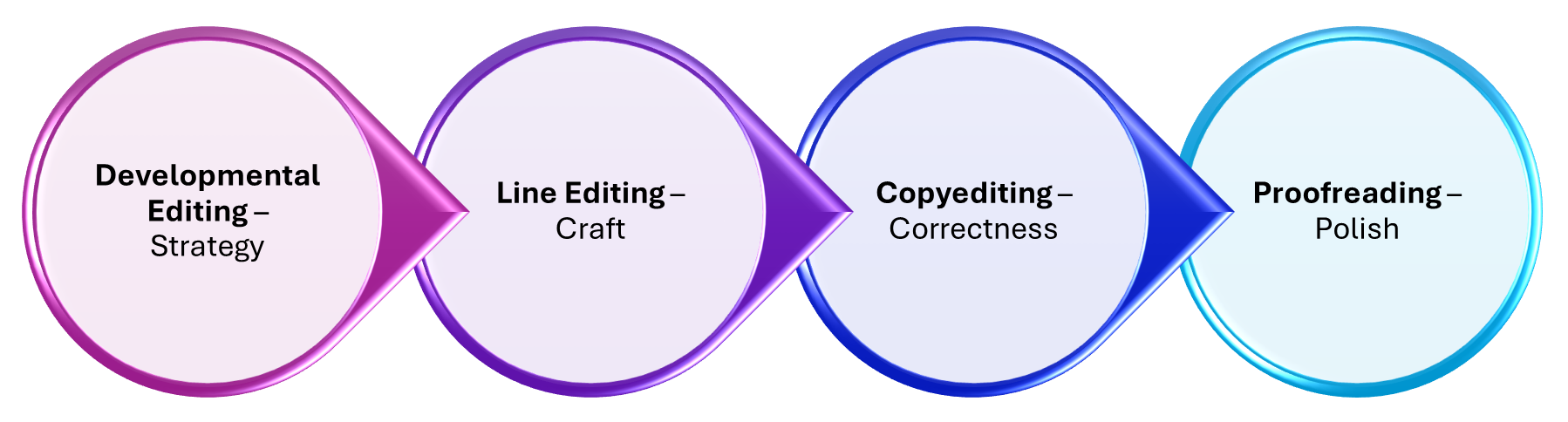

I’m going to oversimplify a bit, but here are the basic types of editing on a spectrum from macro to micro:

Developmental editing focuses on strategy and looks at big-picture questions:

- Does the book structure work?

- Are there gaps in content?

- Does the narrative flow properly throughout the book?

- Are there factual problems or unsupported claims in key arguments?

(You might also hear this called content editing or substantive editing.)

Line editing lives in the “medium” space and focuses on craft:

- Does the language flow at a sentence and paragraph level?

- Is the tone consistent?

- Are word choices appropriate?

- Do facts or references need any clarification, updating, or sourcing?

Copyediting focuses on correctness and ensures technical accuracy:

- Correcting grammar, punctuation, and word usage.

- Checking consistency with a style guide, e.g., The Chicago Manual of Style.

- Verifying consistency in spelling and treatment of manuscript-specific names, terms, and jargon.

- Doublechecking basic facts like name spelling, numbers, quotes, etc.

Proofreading aims for polish—ideally an error-free book—and is the final quality check after formatting and before publication:

- Correcting lingering typos and errors (generally small ones at this point).

- Flagging formatting issues and inconsistencies, for example in spacing or fonts.

- Generally not factchecking unless something throws a big red flag.

It is useful to know these terms, but don’t get tangled up in them. The different types of editing mush together across the spectrum. Line editors could pick up something a developmental editor might normally note; a proofreader might find a problem a copyeditor might have overlooked.

Editors don’t even always agree what each type “should” look like, and different publishers use the terms differently.

What matters most is that you and your editor agree on what kind of support you are getting.

Why you need more than one editor

Do you really need more than one editor for your book? In short, yes. Here’s why:

- Different types of editing take different skill sets. Developmental editing takes more strategic analysis than copyediting. Line editing takes more attention to craft than proofreading. Some editors can work at both a strategic and detail level, but most prefer and are better at a particular part of the editorial spectrum.

- It’s more efficient. Editors look for different issues depending on the stage of the manuscript. It’s far more efficient to address big issues first and work toward the small issues. It doesn’t make sense to spend time copyediting text that a developmental editor might suggest cutting.

- An editor’s eyes wear out. When you’ve been reading and rereading and rereading the same pages, your eyes stop seeing what is really there. Your brain knows what’s intended, so it sees the words it thinks are there rather than the words that are there. Editors have tricks to help (e.g., changing the font, listening to the text), but there’s a point where you are just worn out and need someone with fresh eyes.

- Humans are imperfect. No one editor can catch every issue. Ultimately, the more eyes on the manuscript, the more likely you are to catch errors and inconsistencies.

I often do what you might call a combination of developmental editing and line editing. (I call it “collaborative revision.”) When I finish my work, the manuscript goes to a copyeditor. In a book manuscript of, say, 50k words, my copyeditors routinely find hundreds of corrections and refinements to make.

These are not all errors, but they matter. Trust me—readers would feel the difference between the “clean” revised manuscript and the fully copyedited manuscript.

Deciding what type of editing you need

Do you need to hire editors for all four types of editing? Maybe not, but every manuscript benefits from some editorial support. To decide, I suggest two key questions:

- Where are you in the writing process?

- How are you publishing the book?

Then match your needs to the options.

Where are you in the writing process?

Start by thinking about the condition of your manuscript. Not just whether it is “done.” Does it align to and resonate with your intended audience? Is it complete? Is it well-structured and polished?

Here’s a quick guide:

- A first draft that needs shaping → developmental editing

- A draft that is solid in content but still rough in tone or clarity → line editing

- A manuscript that is ready for cleanup → copyediting

- A formatted interior that is almost ready to publish → proofreading

If you are somewhere in the early drafts and aren’t sure, I’ll tell you that I have never seen a nonfiction manuscript that didn’t need some kind of big-picture work. Even experienced writers need a second set of eyes. You might:

- Hire a developmental editor to help with big-picture revisions.

- Find someone who can do both developmental and line editing with you.

- Get a manuscript critique if you want feedback so you can continue revisions on your own.

If you’ve satisfied the big-picture requirements, you might be ready to move forward with copyediting and such. How you approach those stages might depend on how you are publishing your book.

How are you publishing your book?

Your route to getting your book into the world helps determine the editors you need to hire.

Self-publishing. If you are self-publishing, you must build your own editorial team. At minimum, you need copyediting to meet professional standards and proofreading to catch final errors and formatting issues.

Most authors who self-publish also invest in some sort of developmental or line editing earlier in the process. This is especially important for your first book. (You don’t know what you don’t know.)

Traditional publishing. If you have a traditional publishing contract, once you submit your manuscript, you will likely get feedback on developmental or line editing issues to resolve. Then a copyeditor and proofreader will be assigned for their respective stages.

However, you still need to give the publisher a strong manuscript, and many authors work with freelance editors before submission, especially on structure and content issues.

One of my traditionally published clients worked with two editors before turning her manuscript in. Her publisher was happy with how clean the manuscript was but still assigned three in-house editors, for light line editing, copyediting, and proofreading. So in addition to the author, at least five editors touched the manuscript!

Books are a team sport

Let’s be clear: Needing an editor does not mean your writing is weak!

Creating a book is a team effort—and like any project, it requires different players with different skills and strengths—writers, editors, designers, marketers, and more.

So yes, you need an editor on your team—and most likely more than one!

There’s more nuance to editing than we can address here, so if you’ve got questions, get in touch (info@clearsightbooks.com) and I’ll do my best to answer.