Yours truly in an all-too-common skiing position

In my wilder and [much] younger days, I spent two glorious years as a ski bum in Steamboat Springs, Colorado (peak elevation 10,568′, vertical drop 3668′). As a Midwestern girl, I’d learned to ski on icy artificial snow at Mount Kato (peak elevation 840′, vertical drop 240′) near Mankato, Minnesota, and Fun Valley (peak elevation 1240′, vertical drop 240′), near Montezuma, Iowa.

When I hit the Rockies, my skills were…well, let’s just say there was room for some skill development.

But I forged ahead with pointers from some well-intended and more experienced friends. “Snow plow!” “Bend your knees!” “Keep forward on your skis!” “Make an S!” I continued with crazy speeds, near misses, and the occasional yard sale. I’m astonished I never had a serious injury—I mostly just bruised my ego.

And then came the Winter Olympics. Growing up, I’d always watched the Olympics, but other than clips of excessive speed and “agony of defeat” moments, I can’t say I paid particular attention to the skiing. Now that I lived in Ski Town USA, Olympic skiing was practically required TV-viewing.

So I watched the skiing closely. This time I tried to figure out what the skiers were doing and how they were doing it. Oh!

I finally saw the rhythm.

The next time I was on the slopes, I mimicked that rhythm.

Well, I’ll make no claims about a huge leap forward in my skills, but yes, there was a noticeable difference. I’d started to understand the feeling of skiing. Without closely watching those Olympic models, I’m not sure I would have found that rhythm—or it would have taken me much longer.

(Now of course you are wondering “Why didn’t she just go to ski school like a normal person?” Well, yes. Point taken. But that’s a different topic for another day.)

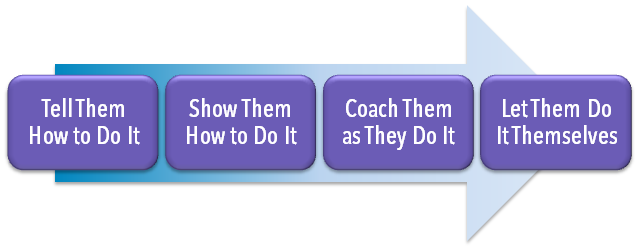

The Four-Step Skill Development Process

Years later in my corporate career, I took a leadership class that offered a four-step model for helping someone with skill development:

- Tell them how to do it

- Show them how to do it

- Coach them while they do it

- Let them do it themselves

Step 1: Tell Them How to Do It

The instructor (manager, coach, etc.) explains to the student how to perform the skill.

- A tennis coach describes the physics of putting spin on the ball and shows how to rotate the racquet.

- A manager takes a class about holding difficult conversations with employees.

- A piano teacher gives a student a piece of sheet music with the notes to play.

Step 2: Show Them How to Do It

The instructor demonstrates how to perform the skill.

- The tennis coach shows a video and demonstrates on court how to put spin on a ball.

- The manager and boss together hold a difficult meeting with an employee; the boss does most of the talking.

- The piano teacher plays a famous recording of the piece of music for the student.

Many adults learn easily and quickly from example, and to me this often-missed step is the one that provides the big “aha!”

Step 3: Coach Them While They Do It

As the learner practices the skill, the instructor offers feedback for correction or improvement.

- The tennis coach offers feedback as the player practices hitting with a spin against the ball machine; then the coach offers feedback during the player’s practice matches.

- The manager and boss together hold a difficult meeting with an employee, in which the manager does most of the talking; afterwards, the two debrief and the boss offers feedback.

- After practicing the piece of music with the example in mind, the pianist plays it for the teacher to critique.

Step 4: Let Them Do It Themselves

Finally the learner reaches an adept (though likely still imperfect) level of performance. The instructor leaves the student to perform the skill independently.

- The tennis player uses the spin technique in tournament matches.

- The manager handles difficult conversations one-on-one with employees.

- The pianist performs a concert.

Once I understood the skill development process, I realized why watching the Olympics had improved my skiing. My friends had given me good information; maybe not enough, but they had told me what to do (Step 1). Then they leapt to Step 3, periodically shouting at me as I made my feeble downhill attempts, and quickly moved on to Step 4, which frankly probably meant they were bored hanging out with such a novice.

I have continued to refer to this model long after leaving that company. It comes into play as I work with beginning writers and advanced writers alike. Where do they need to develop a skill, and how deep do we need to go in each step of the process?

How You Can Use The Skill Development Process

If you have a student, child, co-worker, employee, etc., who is having trouble learning a new skill, ask yourself if you threw them in sink-or-swim style. Or did you give them the needed information, show them what the skill is supposed to look like, and give them a chance to practice with guidance?

If you are learning a new skill and it just isn’t clicking for you, take a look at the process. Did you jump from Step 1 to Step 4? Consider if you need to back up for additional information, a demonstration of the skill, or a coach.

A corollary: If your instructor (coach, manager, etc.) is over-communicating, over-demonstrating, or over-coaching, it’s OK to speak up and say “I want to try it by myself.”

My most recent ski trip was to Appalachian Ski Mountain (peak elevation 4000′; vertical drop 365′) near Boone, North Carolina, a tiny mountain where you can see all twelve trails at the same time (really). It had been a few years, so I decided to go to ski school.

It paid off: no yard sale; no bruised ego.