In Moneyless Society: The Next Economic Evolution, client Matthew Holten posits money as the root cause of our biggest problems today—climate change, resource overshoot, inequality—and he suggests that we need to not just change but rather replace the current system. In short, Matt suggests a world without money.

This is a complex topic and pretty challenging concept for a lot of people, and Matt had to lay out the case clearly and methodically.

Shortly after Moneyless Society was released, I received an extraordinarily kind email from a reader:

The book . . . is excellently written and crafted. . . . Its style of writing and editing match perfectly the concepts themselves: well thought out and crafted, simple and easy to understand, and reading the book and the concepts ARE doable.

As a person with a low level of education, reading is a lot of work. I love to read but I am slow at reading and comprehension. I am also very bad at retention of information. I say all of this because [Moneyless Society] is so well written I was easily able to read and comprehend the information.

Besides giving me warm fuzzies about the work we did with Matt, this email also reinforced for me how crucial clarity is for readers who are new (or newish) to the topic.

What Is Your Audience’s Knowledge Level?

When you think about your ideal reader, you may naturally think about demographics (age, gender, geography) and psychographics (beliefs, values, goals)—and those qualities are important to understand so you can connect with your readers. But also consider their current knowledge level about your topic.

Think about an audience of experts versus an audience of lay people. You expect something different from a scientific paper on regeneration pathways than you do for a nutrition book for the mass market. A financial report for stock analysts has a different feel than a personal finance book for young adults. Experts can jump into the deep end right away. With newer or lay audiences, you must build understanding in a logical progression.

For Moneyless Society, we identified two main audiences:

- People who are interested in but relatively new to the topic, and

- People who are familiar with the topic and want to share the ideas but struggle to explain them to others.

This book was not intended to be an academic treatise for theoretical economists. That helped shape the book.

Techniques for Creating Clarity

At Clear Sight Books, we often find that our clients are writing books for audiences on the “newer” end of the knowledge spectrum, requiring a higher degree of clarity and explanation.

In fact, editor Jenni Hart says, “I always put myself in the shoes of a reader coming in with no prior exposure to the topic. When I make suggestions, I frequently say, ‘Author, you may know this, but your reader does not.’ [Creating clarity] is all in service to the reader.”

Here are several ways to accomplish that knowledge-sharing clarity.

Define new terminology

When introducing new terminology, provide a definition upon its first use. A common practice is to put the term being defined in italics, or sometimes bold. This makes it easy for the reader to skim the text and locate the term.

For example, as Matt begins the discussion of systems theory, he explains:

Systems theory outlines a general progression of systems from simple to complicated and finally to complex, with each level growing increasingly more elaborate and unpredictable.

Simple systems are those in which all elements are easily described and understood and there is a well-defined relationship between cause and effect.

By contrast, if you are writing for an audience well-versed in the topic, it may be entirely appropriate to jump right into using professional jargon.

Additionally, if you define a term early on and then don’t use it for several chapters, consider repeating the definition. I sometimes request that authors add a “6-word summary”—my shorthand for “give the reader a reminder what this is.” If a longer reminder is needed, consider a callout box with the definition. That lets you avoid interrupting the flow of the text but makes the information available to those who need it.

Provide concrete examples

Even though we just defined a simple system, it may still be unclear to you because the definition was abstract. Examples are one way to make an abstract concept concrete.

Matt offers the following examples:

Eating is a system that satisfies your hunger. A shoe is a system that protects your foot. A pen is a system for writing. Once you know how the system works, the results are predictable and easily duplicated. For this reason, simple systems often resemble processes or procedures, such as playing a song on the piano or baking a cake. I know that if I combine certain ingredients and put them in the oven, something at least partially resembling a cake will come out, and not a hippopotamus or Mick Jagger.

(LOL! Mick Jagger! Gets me every time!)

Concrete examples help an abstract idea “click.” Conversely, providing examples and then pointing out the pattern—that is, defining the abstraction—is also useful. By helping readers understand the underlying principle, you enable them to apply the concept in different settings.

Include a glossary

If your book defines a fair amount of terminology, consider including a glossary at the end. One reader who submitted a review of Moneyless Society commented:

I found tremendous benefit in the glossary provided by the author: I believe many misunderstandings in discussion come from a lack of mutual comprehension of terms. . . . This is a great move towards clearing up an individual’s misconception of concepts and something I wish general discourse and other authors provided.

Within the glossary, we cross-referenced terms where applicable. In other words, if one term was used in the definition of another term, we italicized it to indicate that term could also be found in the glossary. For example, here are three related definitions:

Analysis. The taking apart of something to understand the pieces. Compare to synthesis and emergence.

Emergence. The outcome of synergy, the process of things coming together in a self-organizing way and forming something new that takes on properties not found in any of its constituent parts. Compare to analysis and synthesis.

Synthesis. The combination of multiple elements to create something new; the act of understanding the whole and recognizing how individual elements relate to and interact with one another. Compare to analysis and emergence.

Explain figures (charts, diagrams, illustrations)

Any time you use figures—charts, diagrams, illustrations, and so on—regardless of your audience’s knowledge level, it is a best practice to have clear labels, to refer to the figure by name in the text, and to provide a takeaway or interpretation. For readers who are newer to the subject matter, it becomes more important to describe what the figure is showing them.

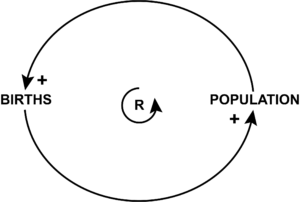

In Moneyless Society, for instance, we carefully explained how to read a causal loop diagram. When it is a simple loop, it is fairly intuitive.

A classic example of a reinforcing feedback loop is the human population. Figure 1 shows a causal loop diagram for that system. In it you will see two simple elements of the system: births and population. The arrows from each to the other show that there is a relationship between the two elements. That is, each one affects the other. The plus signs indicate that, all other things being equal, when one level rises, so does the other; when births increase, population increases; as population increases, the number of births increases.

Figure 1: Causal Loop Diagram of Human Population (Births)

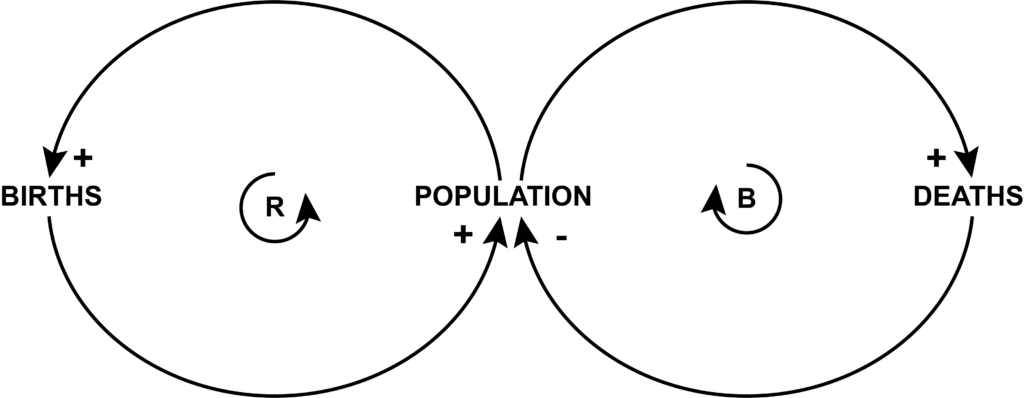

Adding another loop isn’t too complicated:

A balancing feedback loop is one that keeps bringing something back to a certain level or equilibrium. Balancing loops are also called negative feedback loops, though again that does not mean the outcome itself is negative. In Figure 2, we’ve added a second loop to our human population system: to the right of the original loop for births, we now have a balancing loop for deaths, with population as a shared point for the two loops. . . . Now notice how the two cycles interact: as the population grows, there are more deaths; however, as people die, the population decreases.

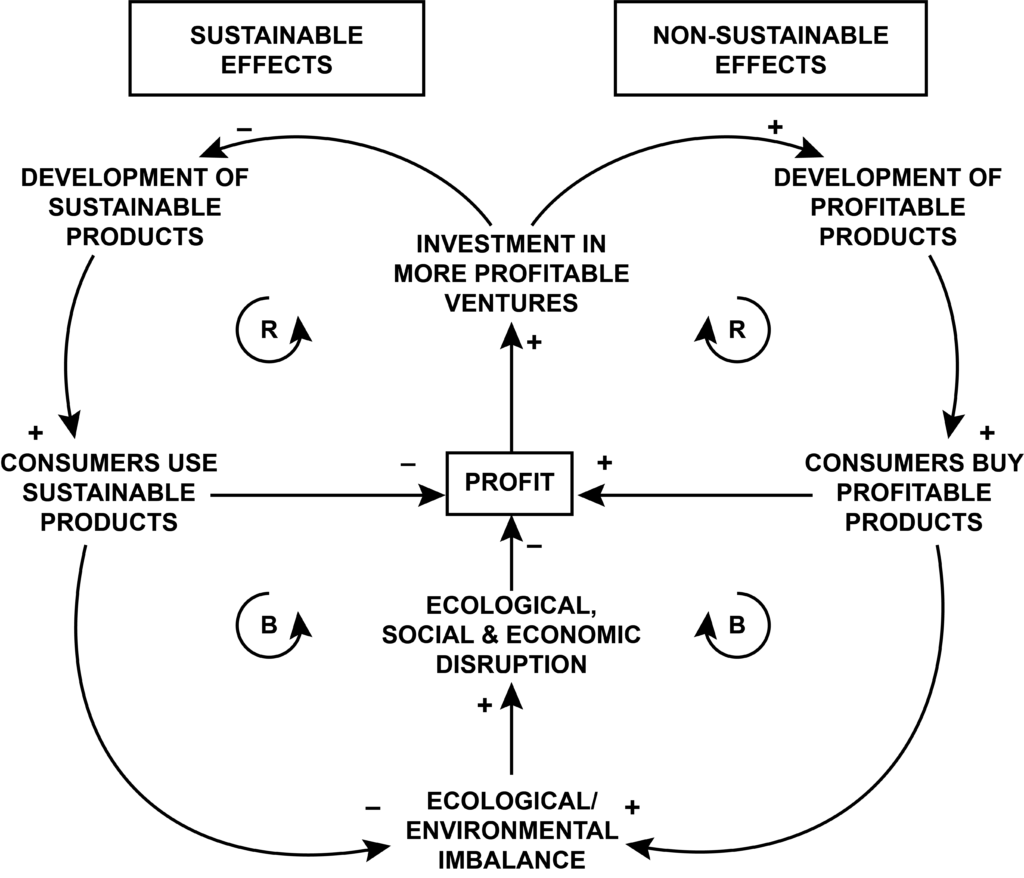

But start adding multiple plus signs and minus signs, and you can easily get confused about what is actually happening. I know I got confused the first time I tried to interpret this diagram:

There’s too much detail to include a full description here, but in the book we described each diagram going from element to element and flagged those areas that might be particularly tricky.

Our hard work paid off. From the same fan email:

The introduction of charts, which I usually can’t understand, added to the written knowledge by offering a different way to think about the concepts, and they were easy to understand.

Move from simple to complex

Our correspondent went on:

I also liked that the charts got gradually more complex to express the concepts and make it easier to get used to reading charts.

This is another approach to use with newer audiences: move from simple to complex. And it applies to concepts as well as figures and diagrams. When you build a house, you start with the foundation and build from there. The same goes for ideas.

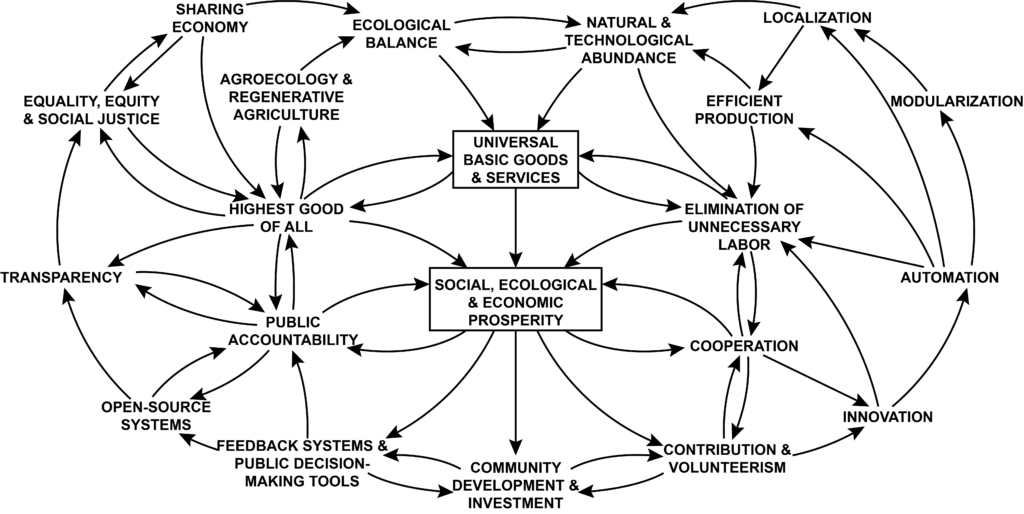

In Matt’s causal loop diagrams, we started with very simple charts to introduce the concept (the single and double loops above), then gradually got more complex (the quad loop above), eventually providing the diagram below—one so complex it was almost impossible to describe other than simply listing the interrelated elements. But by this point the readers had gained the knowledge needed to understand the intent.

Address the objections

With complex issues, addressing common objections head-on aids comprehension by rounding out the alternatives and anchoring concepts among their corollary ideas, some of which the reader may already be holding. Anticipating and removing mental roadblocks can make room for new ideas to be considered.

Some of the objections Matt addressed included “There’s not enough to go around” and “Cryptocurrencies are the solution.” (Um, very recent history would suggest not.)

Said our editor Jenni: “When I came across these in Matt’s manuscript, I was thrilled (a word I rarely use)!”

Share resources

Finally, it never hurts for an author to encourage readers to do their own research. By including footnotes or endnotes and by providing other resources you used in developing your content, you bolster your own position.

In addition to the endnotes Matt used for confirming various facts and statements, he provided a comprehensive list of people and organizations working to advance the subjects he was writing about. From an Amazon review:

Another benefit the author provided, and I believe shows a depth of research in application of concept that I have also not gotten in general in other sources, is examples and links to groups and other entities attempting to live as a moneyless society. I read as much about these entities as I did in the general concepts discussed.

The Bonus to Being Clear

A final bit of our initial correspondent’s email:

I am heavily promoting . . . the book to people across the world. . . . I am planning to assist the physical distribution of the book in New England, making sure that bookstores have them in stock. . . . I have ideas for ways to present the concepts of [Moneyless Society] in new and exciting ways, and the book will always be a great resource and inspiration.

Clarity not only helps your readers understand your ideas—it can get your readers excited to share your book and your message!

After working with an author to prepare their book for publication, holding the finished book is its own reward. But learning that an author’s message is having such impact is a reminder why we do this work.

What’s your change-the-world message? If you’re having trouble sharing it, get in touch (karin@clearsightbooks.com) and we’ll see if we can help.

Recommended Reading

Articles:

Book:

The Culture Map: Breaking Through the Invisible Boundaries of Global Business by Erin Meyer.

I picked up this book when my husband started a new job managing global projects. Meyer identifies eight scales around critical functions—communicating, evaluating, persuading, leading, deciding, trusting, disagreeing, and scheduling—and how different cultures view them. By understanding where your country sits on the scales relative to other countries, you can better understand relationship dynamics and adapt to be more effective. Fascinating.