Friction is a useful tool in the right settings—I mean, it’s nice when your car brakes work, right?—but when friction gets in the way of completing an action (like reading a book), it’s time to eliminate it.

A classic example of friction is poor website design. You try to buy a product on someone’s website and you can’t find the buy button. Once you do, the shopping cart is a nonstandard design and forces you to enter your address multiple times. And then the vendor doesn’t accept your preferred credit card. The result? “This is too difficult. I’m going somewhere else.” And you leave the website, never to return…

All of those things getting in the way of making your purchase are friction.

The Hierarchy of Friction

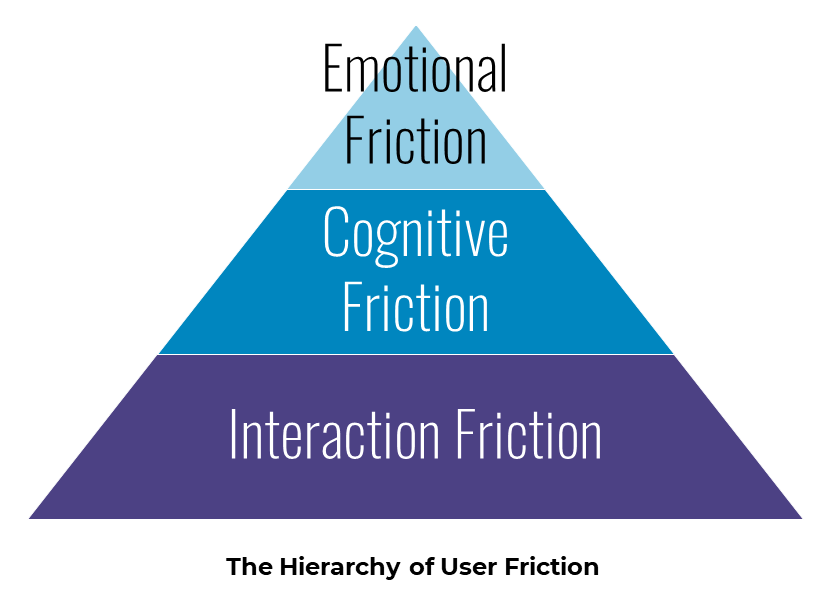

In his article “The Hierarchy of User Friction,” Sachin Rekhi describes user friction as anything that gets in the way of accomplishing a goal in interacting with your product’s interface (he’s writing largely about technology). What I love is that he describes three types of friction, from most basic to higher-level (like Maslow), with the third often overlooked:

- Interaction friction – Difficulty with the interface as in the example above

- Cognitive friction – Anything that increases cognitive load (makes the user have to think harder)

- Emotional friction – Feelings that users experience that get in the way of completing their goal

Your book is a “product” or “interface” no less than a web page is. Indications of friction in your book might include readers saying things like “I can’t find what I’m looking for,” “I don’t get it,” or “It’s just too much.” Once they get frustrated or their eyes glaze over or they feel uncomfortable, they set the book down, never to pick it up again.

(To be clear, we’re not talking about topics that simply aren’t of interest to readers, but rather things they are interested in but friction is getting in the way.)

To keep your readers’ attention, eliminate friction. Let’s look at the three categories of friction that Rekhi describes but in bookish terms: the design of the book (interaction), the writing itself (cognitive), and the feelings readers have about your book or its topic (emotional).

Book Design Friction (Interaction Friction)

Friction in book design is similar to friction on websites: it’s not about the content itself, but rather about how the content is presented. Friction comes from things like…

- Poor font choice – Fonts that are difficult to read or too small cause friction, especially for those of us with reading glasses…

- Margins too small – When the margin in the middle of the book (the “gutter”) is too small, the words get caught in the crevice, making them difficult to read.

- Uncomfortable trim size – I recently read a mass market paperback in which the trim size was taller and narrower than usual. This made it difficult to get the book to stay open. Proportionally, the pages needed to be wider for the book to have enough “give.”

- Forcing the reader to go outside the book – In a book contest I judged, one author referenced her website for worksheets but didn’t include even the basics of them in the book. So if the reader was lazy (like me), they completely missed important information.

- Information in an inconvenient location – Have you ever read a book with endnotes and found yourself constantly flipping back and forth from the main text to the back of the book? So frustrating! Those types of explanations would probably be better as footnotes. Similarly, footnotes that are simply citing sources would probably be better as endnotes so they don’t keep interrupting the text. Guideline: Put information where it is easily accessible but not in the way.

Design entails subjectivity and judgment, so always consider your intended audience to make design decisions that best serve them.

Writing Friction (Cognitive Friction)

The following list of things that cause friction in writing should look familiar. But instead of thinking of them as “grammar” or “craft,” thinking about them as “cognitive friction” may help decide how to address them—and the importance of doing so.

- Lack of clarity – Lack of clarity might show up as a poorly explained concept or as flowery language that obscures your intended meaning. Either way, lack of clarity makes your readers have to work too hard.

- Poor structure and flow – In general, we read linearly, beginning to end. If readers get lost and have to backtrack to find needed information, there’s a problem with the structure. (And I’m not talking about mysteries or novels where the misdirection or nonlinearity is intentional.)

- Unnecessary arguments – Anything that causes the reader to argue with you unnecessarily, such as factual errors or unsupported claims, is a form of friction.

- Too many words – When a writer uses too many unnecessary words, reading becomes a slog. Challenge yourself to trim 10-15% of your words without cutting anything material.

- Dull language – Without variation in sentence length, pacing, and vocabulary, reading a book can feel like listening to a monotone speaker. You can still get the needed information, but you have to work hard to stay awake while doing so.

- Excessive repetition – We all have our pet words (really, well, so), verbal habits (parenthetical asides, phrases like “The fact of the matter is…”), and punctuation tics (em dashes, ellipses). These aren’t errors, but they can become annoyances when used too frequently.

- Errors – We all make occasional mistakes, but every error causes the reader’s brain a tiny moment of mentally correcting it, and at some point the author loses credibility.

When I critique or edit, I’m always looking for ways to eliminate friction so that readers can take in information rather than struggle with it.

Emotional Friction

Emotional friction is more challenging to describe than the first two categories. I can’t give you a neat list of “do this, don’t do that.” I was tempted to include the last couple of items on the cognitive list here because they cause me personally so much irritation (LOL), but that’s not quite the type of emotion we’re talking about here.

What causes emotional friction in books? Here are a few real examples I came up with, but you may think of others relevant to your book.

- Difficult topics – Some books can be difficult due to the sensitive nature of the topic for the reader. For example, Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist is difficult to read because it exposes biases that we may not even know we have. By clearly defining terms and sharing his own journey about concepts he now considers “racist,” Kendi allows the reader to approach the material with greater openness, making the ideas easier to access. Assess whether your topic is one that may cause a feeling of vulnerability or discomfort for readers and how you might mitigate that.

- Authorial tone – The tone the author uses can alleviate or aggravate emotional friction—and can sometimes create friction where it may not have existed. For example, I read John Gardner’s book The Art of Fiction because I wanted to learn about writing in that genre—no friction to start! But the sexism in his writing was incredibly irking. In the end, the value of what he said kept me reading, but no doubt the read was harder than it needed to be. (My review, if you’re interested.) Assess whether your tone supports your goal. For instance, if you’re trying to lay out a business case for a major systemic change or why your profession needs to change standards, ranting about the current system is less effective than objectively laying out the facts that support your proposal.

- Overwhelm – Readers may experience overwhelm at the magnitude of your book’s topic, or they may be experiencing overwhelm in their personal life, or both. For example, Becky Sansbury’s book After the Shock is directed at people in crisis. She strategically broke the book into small, easily digestible pieces so readers could dip in and out for advice. She also used a supportive, conversational tone.

Emotional friction is more invisible than the other two forms, so you need to know your audience well to understand why they might hesitate to read or finish your book.

How to Find the Friction so You Can Eliminate It

There are several ways to find friction so you can eliminate it.

- Know your audience – Develop personas or do some other form of audience analysis to understand their situation, wants, and needs.

- Revise, revise, revise – Make the writing the best it can be on your own. Use all the normal editing and proofreading tools that help flag grammatical problems, verbosity, clarity issues, and so on—Microsoft Word’s editor (spell check, grammar check), tools like Grammarly, and reading your book aloud to identify things you stumble over.

- Get feedback – Ask for feedback from your writing critique group, a writing coach, editor, or beta readers. In your request for feedback, include the question “What’s getting in the way of your engaging with this book?” This can help especially with cognitive friction but may also help with emotional friction. Then of course, you may need to revise.

- Understand book design – Finally if you’re self-publishing, learn book design or work with an experienced designer who can point out problems and help you avoid major missteps.

Identifying and eliminating friction in your writing can take time and practice. But the better you get at reducing friction, the more your audience can engage with your book’s content—and you’ll keep your readers’ attention all the way to the end.

Not sure where your book manuscript has friction, or want help eliminating it? Get in touch at 919.609.2817 or karin@clearsightbooks.com.