I learn something on every book project I do, whether it’s the subject matter itself or something about the craft of writing and publishing. Recently I learned about book indexes while working on the second edition of Philippos Aristotelous’s The MARVEL of Happiness.

I am far from an expert, so in this article I simply want to share some book index basics to give you an easier start than I had.

What is a book index?

An index is an alphabetized list of terms and subjects in a book with corresponding page numbers where those subjects are located, but an index doesn’t cover every term and every subject, or every occurrence of one. An index is designed to be a map of pertinent information and to break down denser subjects for readers so they can quickly find what they are looking for.

Assessing what should go in an index and designing it to be useful may not be as easy as you think. For The MARVEL of Happiness, we turned to professional indexer Heather Pendley of Pendley’s Pro Editing. I found Heather extremely helpful in understanding how indexes work and what to consider in hiring an indexer.

Two types of book indexes

Surprisingly, one of the trickiest things for me to figure out was how to ask for what we needed in Philippos’s book. We knew we wanted an index in the print book, and we also wanted one with hyperlinks in the ebook. Heather explained to me the correct names . . .

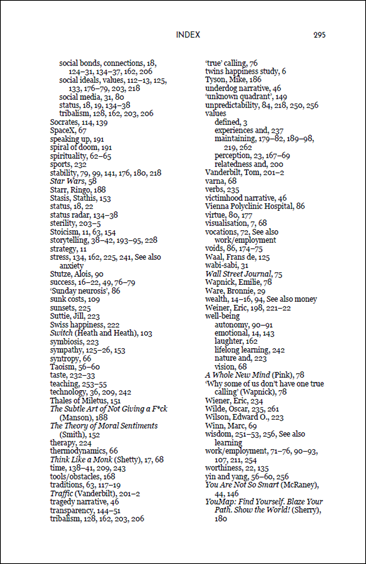

A back-of-book index, affectionately abbreviated BOB, is the standard index you find at the back of print books. Here’s a page from the index in The MARVEL of Happiness. You’ll probably recall from using them that indexes are typically in columns, many entries have multiple references, and there are cross-references (“See” and “See also”).

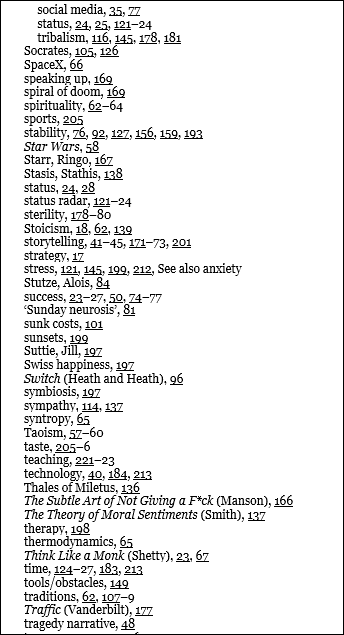

An embedded index provides the same information as a back-of-book index, but contains live links on the page number references so ebook readers can jump from the index entry to the location in the text. (These links come from hidden codes that the indexer adds to the relevant word or phrase in the source document; the codes then populate the index.) In the image of the MARVEL ebook index below, all the underlined page numbers are hyperlinked to the text.

(You might be thinking “Wait, ebooks don’t have page numbers.” Correct. The page numbers correspond to the pages in the source file, usually in Word or InDesign, and are basically irrelevant in a reflowable ebook. But they still get the reader to the correct location and do double duty for a BOB when the book is printed.)

A back-of-book index is usually the default. If you have an ebook, embedding is an additional cost, but you end up with both an embedded and a BOB index. Some people (and publishers) create the BOB but skip the embedded index. (Should they? Maybe not, but the embedded index can cause some technical headaches that I won’t go into here, so I can see why they would.)

Does your book need an index?

I asked Heather which books needed an index, and she responded that most nonfiction books would probably benefit from one. In particular, books that are longer, more academic, and/or that will be used as a reference (e.g., a cookbook) benefit from an index. Potential book buyers frequently check out the table of contents and the index to see how “serious” a book is.

In Heather’s words, “A well-written index can increase book sales and deliver greater value to readers.”

For shorter nonfiction that is lighter and more straightforward, you may be able to skip the index, especially if there is a detailed table of contents or headings that make the book easy to skim.

Think about your book: is it reasonable to expect a reader to guess in which chapter a particular reference is located? Maybe so for shorter books, but not usually for longer books. For Philippos’s book, which is heavily sourced and draws on many different thinkers on the subject of happiness, an index was a useful addition.

By contrast, in Becky Sansbury’s After the Shock about crisis and resilience, we instead provided a supplemental detailed table of contents. The book structure and heading levels were clear and thorough and would likely get someone to the right chapter fairly quickly.

I’ve also worked on many books where an index did not seem warranted. It all depends on your strategy: what is your intent for your book and how do you expect your readers to use it?

Where indexing comes in the publishing process

Indexing is typically done when the interior of the print book is designed and formatted, and the page numbers will no longer change. This means the text is finalized. The only thing that might remain is a final proofread of the formatted manuscript.

(If the indexer is making an embedded index, they could potentially begin earlier in the process, e.g., before formatting is complete. I’m not sure I would recommend that unless everyone involved is experienced and understands version control. And if you don’t understand what I just said . . . make sure you work with someone who does.)

The indexer essentially reads the book as an actual reader would, assesses the information that is relevant for an index, making note of the page(s) upon which it is found, then compiles and organizes the information—that is, they write the index.

It’s important to note that while the indexer uses software that helps automate the creation of the index, the assessment process itself is not something that can be automated. This is a human function that brings in life experience and education to understand references that a computer/AI would miss.

Depending on book length, you can anticipate two to four weeks for the indexing process. Many indexers are booked a couple of months out, so make sure you schedule them early enough that you don’t get caught having to wait.

Additionally, don’t make changes after this point, or the index may need to be corrected!

When you get the index back from the indexer, it may be a separate document that gets added to the book, or it may be incorporated into the actual design file. Either way, you (or your designer) will probably need to format the index in terms of font, columns, and so on. And if it is an embedded index, you may need to understand how to link all the entries (which is beyond the scope of this article).

Resources for finding book indexers

There are several professional associations where you may find qualified indexers. And, yes, there are courses and certificates for indexing—it is a skill that comes from both experience and training.

- American Society for Indexing – This is where we found Heather.

- Society of Indexers (UK and Ireland)

- Indexing Society of Canada

- Editorial Freelancers Association

- Reedsy

As you research possible indexers for your project, look at:

- Subject areas – Different indexers specialize in different topics. For instance, Heather works with nonfiction, primarily business, finance, and academia; she doesn’t work on politics or religion.

- Type of index – What do you need: just a BOB or both a BOB and an embedded index? Not all indexers create embedded indexes.

- Software – Indexers use special software to create indexes. That software may or may not matter to you, but the design program you use for the book interior may matter to them, especially for an embedded index. We used Word on this project, but we use InDesign regularly as well.

If you are new to indexing, as I was, ask as many questions as you need so that you have clear expectations, know what to do/not do, and aren’t surprised by anything in the process.

Price range for book indexing

Indexers tend to price by “indexable page”—meaning the formatted page that has text in need of indexing. This is different from the raw manuscript page in Word, and it excludes pages that don’t need indexing, e.g., acknowledgments.

For BOB indexes, in my research I commonly saw $4 to $5 per indexable page (of 250 to 300 words), depending on the density of indexing required. So a 200-page book might run $800 to $1,000.

For embedded indexes, which include a BOB index, I commonly saw rates of $6 to $7 per indexable page. So adding an embedded index to our 200-page book would bring the price to $1,200 to $1,400, but again, you get both types of index for this price.

You may find other pricing approaches, e.g., flat rate or per word, and the price will vary by the indexer’s expertise, depth of subject matter, and turnaround time, but those ranges give you a reasonable idea of what to expect.

A few final notes on book indexes

You might be wondering, “Can’t I just do this myself? After all, I know the book!”

In short, no.

To expand, Heather says, “While the author is the expert on their subject, they are generally too close to it and lack familiarity with what makes a good index and the indexing process in general. A professional indexer can be objective, making an index more useful and valuable to readers. When indexing isn’t someone’s specialty, the index will take longer and not be as useful as if they hired a professional.”

She compares it to tiling a bathroom: you can buy the correct supplies and follow instructions in the how-to book, but it will surely take longer, probably not look as nice, and may even cost more than having a professional do it.

It might be appealing to attempt the index yourself, especially if you are technologically savvy or if your traditional publisher has put the onus of indexing on you, the author. (Yes, the author often bears this cost in traditional publishing.) But a bad index might be worse than no index. I have a cookbook where the index is so useless it’s frustrating. You don’t want your readers to have that experience.

Heather did a great job creating the index for The MARVEL of Happiness. Philippos’s comment: “It looks quite rich!”